(Re)Views from Lagos – African International Film Festival 2018

A western with a South African Robin Hood, a documentary on poetry and a take on race relations in Tanzania. Eight film reviews written by Nigerian participants of a workshop organized by Goethe Institute Lagos.

Founded in 2010, the Lagos-based African International Film Festival has since become one of the most important showcases for African cinema on the continent. This year, concomitant with the festival, a workshop for young Nigerian film critics was held at Goethe Institute Lagos. For their final assignment, the participants were asked to review one of the films seen at the festival. Below are eight contributions, focusing on five very different films. The workshop was designed and prepared by Aderinsola Ajao and facilitated by Lukas Foerster.

---

Hello, Rain (C.J. Obasi, Nigeria, 2018)

Turns at film school have taught a new generation of Nigerian filmmakers the nuts and bolts of making visual spectacles. This new facility with the technics of filmmaking, the controversial filmmaker and critic Didi Cheeka will tell you, has come at the expense of Nollywood’s previous facility with story. Can the new generation spin a good yarn? We might be getting ahead of ourselves here. The very first question to ask, if C.J. Obasi’s Hello, Rain is anything to go by, is if this new generation can even spot a good story at all.

Visually, Hello, Rain is a masterful work. If its aesthetic is not quite specifically Nigerian, it certainly is an iconoclastic take on the as yet elusive task of creating one, and maps out a territory for Obasi that is all his own. Obasi claims African futurism as the organizing principle of his creative vision. That, on current evidence, seems more the wrapping than the candy itself. (What, one might be tempted to ask, is so futuristic in a culture where metaphysics have always been mind-bending and teleportation and time travel are concepts as old as time?) Yes, the colorfully clad characters wear lurid wigs which are a mesh of incantation and code. Yes, they shoot concentrated laser beams from their eyes. But what is African or futuristic about any of this given the plenitude of where we are coming from?

The problem with Hello, Rain stems from its source material. Hello, Moto, Nnedi Okoroafor’s 2011 what-will-one-call-it, is more an anecdote than a short story. Its central conflict is simplistic, if it can be called a conflict at all. One of three contented friends suddenly decides to make wigs—“to make things better,” she claims—which makes things far worse when worn by the trio. They fed conflict and are pillaged for personal profit, profit expended in the luxurious bosom of Paris.

Told, inexplicably, from all three of their perspectives, the rest of the story is a stilted, heavy-handed attempt at allegory, an unfurling of the creator’s attempt to undermine the power of her creation—“the story of how the smart woman tried to right her great wrong.” The resolution is a cliffhanger where good and evil smash into one another. Fidelity was always going to be a problem.

In the Q&A following Hello, Rain’s screening at the 2018 AFRIFF, Obasi’s excessive reverence for Okoroafor is clear. The outcome of this reverence is an adaptation practically indistinguishable from the original, which is unfortunate because, despite its gorgeous exterior, it exhibits a poverty of suggestion and recapitulates all of Hello, Moto’s deep flaws. “Is this gorgeous exterior,” Longinus wondered many centuries ago, “a mere false and clumsy pageant, which, if laid open, will be found to contain nothing but emptiness?“

Kayode Faniyi

---

Sew the Winter to my Skin (Jahmil X. T. Qubeka, South Africa, 2018)

With Sew the Winter to my Skin, writer-director Jahmil X. T. Qubeka attempts to flesh out the character of the historical outlaw, John Kepe, from his own perspective. It is obvious from the direction of the film that Qubeka is impressed by John Kepe's legend. Still, the director does not cast him as a completely perfect character but rather sketches out Kepe's humanity beyond the legend. This act of humanizing the legend – showing his weaknesses alongside his strengths – becomes especially clear in the scenes in which Kepe relates with his own family.

After a bizarre opening scene, when a monstrous looking being jumps out of the bushes fleeing white men with guns, the film sets about framing the entire spectacle in a freewheeling form using little dialogue and plenty of action. As this is an apartheid era film, race is, of course, a big part of the story and where dialogue or human sounds do exist in the film's world, it is mostly the black 'natives' shouting in protest or mourning or warning. Guns and whips, meanwhile, seem to carry all the needed work of communication on the part of the white oppressors.

John Kepe (Ezra Mabengeza) is reminiscent of the white men's daring in coming to evict the natives from their land. Kepe is stealing mostly livestock from their houses and giving it to his people for their cultural rite of passage rituals. In doing that, he becomes a face for the resistance – buckling clearly against the oppression around him. He is an outlaw fitting for the film's obvious reach towards the Western genre as he flees through fields on horseback, his pursuers hot on his trail.

Those pursuers include Peter Kurth as Gen. Botha, a Nazi sympathizer who is himself trying to outrun debt and has to contend with a drunken wife desirous of home. There is also the mean spirited Black Wyatt Earp acted by Zolisa Xaluva – a black man with unexplainable power who is set apart from his people by his implication in their oppression while being at the same time devoid of the one thing (white skin) that will make him fully accepted by his chosen comrades. Black Wyatt Earp is one of the many characters in the film that would have benefited from further exploration, but the director seems willing to merely sketch around any character outside of Kepe, leaving a lot of holes for the audience to fill.

In the scene in which Kepe proposes to his wife, we enter his cave for the first time. An excited Kepe lights up the space, setting the mood for his wife to be and at the same time revealing to the audience the extent of his escapades. Brenda Ngxoli as Kepe's wife wears unease and fear like a second skin and practically flees in the face of what life with Kepe will mean; an action that will set the tone for Kepe continually negotiating with her for affection in their home (although he seems to win frequently as evidenced by the number of children in their home). These negotiations as well as John Kepe's penchant for running and hiding when the results for his actions materialize, allowing others to bear the brunt of consequences, lessens the impact of his influence and bravado, perhaps making the statement that he is only human after all.

Quebeka's very visual interpretation of this historical figure is often loose on details, but what is mostly shown – helped by great music and little dialogue – is enough to capture the legendary energy of John Kepe that was at odds with the time in which he existed. This energy plays very well on screen, especially with the superb cinematography of Sew the Winter to my Skin.

Obianuju Okafur

---

South Africa’s official entry to the highly competitive Best Foreign Language Film category is the enchantingly titled Sew the Winter to My Skin. There is little enchanting about the plot though, a blend of violence, racial tensions and inequality that had begun to be institutionalized in pre-Apartheid era South Africa.

Films with high-minded (read: Oscar) ambitions coming out of Mandela country tend to dwell on the country’s rich and traumatic history. Think Darrell Roodt’s Yesterday which followed a mother dying of HIV, Gavin Hood’s Tsotsi, an ultimately hopeful account of slum dog living and last year’s Inxeba (The Wound), a potent examination of toxic masculinity with a lightning rod socio-cultural background.

Sew the Winter to My Skin does not court controversy in the way that writer-director Jahmil X.T Qubeka’s Of Good Report did back in 2013, but that doesn’t mean the story is any less compelling. It is based on true accounts of the life and times of John Kepe, a self-styled “Samson of the Boschberg’’ who, in his own way, sought to upset the establishment.

Sew the Winter to My Skin presents Kepe, a Xhosa outlaw who stole from his white, wealthy neighbors, as some kind of cinematic hero seeking some redress for the economic imbalance. White colonial land owners bore the brunt of Kepe’s pilfering ways and for this narration, the 'villains' are represented by General Botha (Peter Kurth), a war hero and Nazi sympathizer.

Qubeka’s screenplay isn’t particularly concerned with fleshing out any of his supporting characters and indeed, even his leading man, played with loads of expressive physicality by Ezra Mabengeza, is ultimately given short thrift. There are repetitive scenes of Mabengeza’s John Kepe fleeing from his hunters – sometimes with a sheep dangled across his shoulders – but too few that dig into the core of Kepe’s story.

Kepe is physically present but the movie is only interested in the broad strokes of his character. The supporting characters, from Bongani Mantsai’s battle-ready Fearless, Zolisa Xaluva’s “Black Wyatt Earp” to Kandyse McClure’s Golden Eyes, are vividly rendered, named for a particular striking feature or trait. But none of them is given room to blossom into anything other than crutches to hold the thin plot. McClure’s Golden Eyes for instance seems like she would have an interesting back story and in the scene she shares with Kepe, there is chemistry to burn. But the film ultimately is disinterested in pursuing anything significant from the character.

The outcome of the twelve-year manhunt for John Kepe is a matter of public record. To keep things fresh – and audiences engaged – Qubeka presents his film in a non-linear, time-scrambled format that makes little use of plotting.

Technically, Sew the Winter to My Skin is excellent. The vistas and nature shots are ravishing and Jonathan Kovel’s cinematography lights up the characters in ways that are striking, but he manages to keep them unknowable and at a distance at the same time. Dialogue is kept to the barest minimum as actors work with their faces and bodies, yet the film never for once feels like a gimmick. This form of arrangement only means that other senses are activated as well and the cinematic experience is even more rounded. The result may be lukewarm, but Jahmil X.T Qubeka is ready for the big leagues.

Wilfred Okiche

---

In a racially charged and violent 1950s rural South Africa, a liberal journalist recounts the epic chase, edge-of-your-seat capture and intriguing trial of a flamboyant, native "Robin Hood". His captivating re-imagining paints a portrait of a divisive outlaw, hunted by the Republic, elusive even to his loved ones, all whilst remaining a champion of the disenchanted. Selected as the opening film of the 2018 Africa International Film Festival (AFRIFF), Jahmil X.T. Qubeka’s sophomore outing follows a path similar to that of his first film, Of Good Report (2013), where a lot of silence and minimal dialogue was employed. OGR made quite a splash at the 2013 AFRIFF with the Nigerian audience.

Based on the true story of John Kepe, the "Samson of the Boschberg Mountains", the story is set in the 1950s, a time when South Africa was fraught with apartheid and black South Africans lived in servitude to the white interlopers. Kepe served as a rebel and Robin Hood figure to his people, stealing from the war hero turned sheep farmer General Botha, keeping him and his men on their toes. In the grand scheme of things, stealing one sheep at a time does nothing to change things for his people, but it brings hope in a “stick it to the man”-manner.

Starting from the trial of Kepe, the non-linear narrative is a bit hard to follow at times as you really don’t know the motivations of some characters and exposition dialogue is nonexistent. This director wants to make you work and connect the dots. Aside from Kepe, there is a Caucasian journalist following his trial, trying to understand his story, mythology, but he, too, never speaks a word as we follow his arrival, when he is delivering letters from Kepe in prison to his wife. He acts as a sort of bridge for the different narrative strands.

The film is beautifully shot, like a Golden Age Hollywood Western; wide landscape shots, scope of scenery, the hero escaping on a stolen horse as the posse gives chase. It might be the kind of film that would have been made at the height of the Western, if a Native American was the protagonist in the Robin Hood role, against the white invaders who occupy the land of their ancestors.

This film takes the rule “show, don’t tell” quite literally. Not one word is exchanged for long, extended scenes, but body language, gestures and the framing of the characters tell us all we need to know. We see Kepe's relationship with his wife through tears and body language as she isn’t completely comfortable with his heroics and the danger it brings to their family.

Those not familiar with South Africa’s history may not grasp the significance of what he was doing and what it meant to be black in then-Rhodesia. There is a lot going on in the film and not all of it completely ties together. As South Africa is still a place with a lot of racial tension and most of the economic power is still held by the Caucasian minority, Sew the Winter to My Skin may remind the people of a hero who took back what they deemed was rightfully theirs.

Most characters are archetypes for many roles in South African life over the years. They represent the face of tyranny, oppression and, in the case of a mustached cowboy credited as "Black Wyatt Earp", racial betrayal. The latter is a character who never says a word but has such a cool presence, you are almost rooting for him, until you remind yourself he is an oppressor of his own people.

Other characters aren't given names but are identified by traits or physical descriptions: Golden Eyes, Scarfaced Kid, Old Matriarch are placeholders and mostly have no agency apart from reacting to the actions of Kepe, whose own motivations we don’t fully understand as we try to figure out how he was captured.

Qubeka is clearly an ambitious filmmaker to watch and we will see if Hollywood tries to scoop him up, like it did his fellow South African, Gavin Hood. Sew the Winter to My Skin is South Africa’s official entry to the Oscars for Best Foreign Film, time will tell if it can repeat the success of Tsotsi (2005) and bag another prize for South Africa.

Olu Yomi Ososanya

---

The Poets (Chivas DeVinck, USA/Nigeria/Sierra Leone, 2017)

Director Chivas DeVinck’s The Poet, a documentary on the lives and writings of two West African prolific poets is spontaneous, a good shot and a communicative journey down memory lane. It takes the structure of a kunstlerroman, exploring Syl Cheney-Coker and Niyi Osundare’s formative years and their coming to maturity. The camera follows the two poets as they return to their childhood homes, their schools, and their universities, describing in clinical precision what has shaped their art. Along the way, impactful political traumas are explored with short bursts of archival footage; the Sierra Leonian civil war and the military rule in Nigeria are some of the examples. In the documentary, poetry is the true protagonist. A few times over the course of the film, both poets read evocatively as the camera pans across related and unrelated imagery. The poems are simultaneously inscribed on the screen, giving the documentary a richly layered, intertextual and intermedial experience.

Running for 1 hour and 40 minutes, the documentary brings the duo together and sends them off on nostalgic trips in their respective countries; Freetown for Cheney-Coker and Ikeri-Ekiti and Ibadan for Osundare. The structure is subtly straightforward and very well thought out. It is divided into a first half of the journey unfolding in Sierra Leone with Cheney-Coker as the interlocutor a second half in which Osundare takes us through several parts of Nigeria. The Poets makes very particular, decisive stops.

The film begins in a car as it navigates the narrow Freetown streets. Cheney-Coker is the dynamic, informative guide and Osundare is a teasing, affectionate and curious tourist. The tone is immediately jolly and infectious: here are two genial men brimming with anecdotes ranging from serious to completely facile, needling each other but also learning from each other. As they make their way through the city, Cheney-Coker points out how the war in Sierra Leone has marked everything. Wide, panoramic shots of the densely populated and hilly city along with Cheney-Coker’s intimate memories of the space allow Osundare and the viewer to have an affective experience of the geography.

We see Cheney-Coker’s childhood home built in 1936, which he has reclaimed since the end of the war. Old books abound in the modest, crumbling interiors and soon a visit to his school rounds out the importance of a truly literary education. The camera eventually turns its attention upon the sea. With the views of the Atlantic Ocean, slavery’s omnipresent haunting comes into the picture. “If there was no ocean, there would be no Syl Cheney-Coker’s poetry,” Cheney-Coker explains. DeVinck gives us our first beautifully choreographed poem sequence: Cheney-Coker reads one of his well-known poems called “The Breast of the Sea” as a boat glides over gentle, sun-sparkled waves. The music sets the tone for a grim memorializing of “our bloody century” and the orphans, pain, tears and suffering it has left behind.

The documentary successfully seals the connection between place and poetry, and it is through reciting particular poems in carefully chosen public and intimate spaces that evocations about history and humanity are allowed to emerge. The history of slavery in West Africa, the history of war, the centrality of the sea as ethos and identity as well as personal reflections on marriage and love are folded into the fabric of these sequences. An incisive montage also takes the audience through Sierra Leone’s brutal history of diamond mining. “Shameless stone, bloodletting woman, I could have loved you, but I give you up for the feverish lust of the world!”, Cheney-Coker reads. Integral to several of these poems are the politics of Africa’s colonial history and its resounding, almost incalculable impact upon the present.

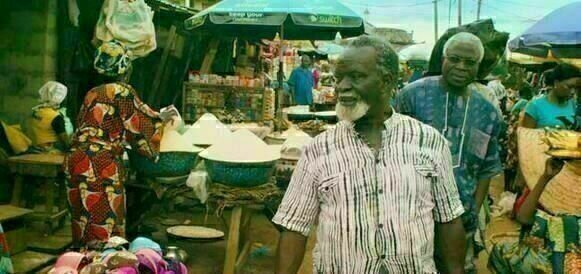

The duo is suddenly in the car again, this time in a traffic jam in Lagos. Osundare becomes the poet-guide taking us through Yoruba states. Familiar tropes and themes come and go, visits to schools and universities, the formative years in childhood homes and the profound importance of education. But Osundare’s Nigeria is more ceremonial and bustling. Several friends and family members crowd around and even into the camera. The welcome rituals are grander and longer. There is an international poetry festival where Osundare is shown as a revered and honored member of the community. We learn that just like the Sierra Leone war for Cheney-Coker, Hurricane Katrina figures as the psychic wound in Osundare’s life.

In the second half of the documentary, there is a real deepening of the conversations about poetic form and political poetry, the debate on African languages, the literary canon inherited from colonialism and the many problems that plague their beloved continent. We are in Nigeria, so the poets are predictably perturbed by the fact of poor governance in several African countries and the question how to combat corruption. Primarily, though, The Poets is an impressive homage to storytelling. Tales weave and wind through the documentary, always engaging, delightful, emotionally and intellectually rich. It is evident that the poets are completely committed to and deeply steeped in oral traditions, in the act of recounting stories and reciting poems.

The poets also engage with the fraught relationship between poetic form and political engagement, a tension that remains at the core of Western understandings of poetry and literature, and one that they both clearly inherited from years of being marinated in what passes as canonical and classical. “All literature is protest literature, in some form or another,” declares Osundare. “The most sublime form of art is the protest against silence. The real issue is what or whose politics. You know, I’ve been called a political poet. There was a time I used to be concerned about it. Now I claim it as Christians who say, 'and I embrace this!' Oh yes, it’s political! Why not political? My very presence on this earth is political. My existence as a black person is political. The language I use itself is political. The choice is political.” These declarations aside, it is the documentary itself which becomes evidence of the ways that the poetic and the political are fundamentally interwoven. Not only are the poets completely imbricated in a complex and demanding socio-political sphere, their poetic practice draws from it and simultaneously nourishes it.

Films about poets are not necessarily commonplace, but the poetry documentary is a fairly established minor genre, especially in the past decade or so with the rise in popularity of spoken word performances. Within that, any engagement with African poetry is particularly rare. In fact, several generations of African poetry have not gotten the attention they deserve in academic and literary spheres. The Poets reclaims and revives that space, making it pulse with life and potential.

With their backs to the viewer, Syl Cheney-Coker and Niyi Osundare sit on a balcony at Osundare’s home in Ibadan, with a glass of wine in their hands, they toast to poetry, to their dynamic past and their futures, to their friendship. They look out ahead as the pouring rain beats down upon a half-constructed building but keep turning their heads around to recount something or other. This retrospective positioning, looking ahead but simultaneously gazing back, is the precise mode of this literary documentary.

At the end of the film, the toasts soon turn into a conversation with the film’s director and Osundare asks the question which the audience has been wondering about for the past hour and a half. “Why did he choose us two out of the pantheon of African literature?” It is certainly a curious choice, but it manages to whet the appetite for a series-like project. Perhaps two East African poets will be the subject of DeVinck’s next documentary. The film fades to credits and the questions, hopes and poems continue to hang in the air.

Chinyere Okoroafor

---

T-Junction (Amil Shivji, Tanzania, 2017)

The social dynamics of Tanzania’s multiracial society take prominence in Amil Shivji’s T-Junction (2017). Set in Dar-es-Salaam, T-Junction examines these intersections through two major characters: Fatima Hirji (Hawa Alisa), the disillusioned daughter of a recently-deceased alcoholic with a Gujarati background and Maria (Magdalena Christopher), the daughter of a street vendor whose mysterious injuries confine her to the public hospital where she and Fatima begin a bizarre companionship that proves pivotal to the film’s plot.

Initially, T-Junction seems to be about Fatima’s dysfunctional relationship with her late father, Iqbal, the tension caused by her inability to comprehend her mother’s decision to mourn such an irresponsible and unworthy man, as well as her hostility towards a female relative named Bhabi. However, a chance meeting with the eccentric Maria at the local hospital gradually changes the narrative from tragic to comical, as Shivji introduces Maria’s home at T-junction, her family and friends as well as their run-ins with the city officials who are hell-bent on implementing a government ban on street trading.

As the scenes switch from Fatima’s dreary existence in an Indian-dominated neighborhood to the hospital that serves as their rendezvous and Maria’s T-junction, various prejudices come to the fore: while Maria and her friends from T-junction suffer the brutal, oppressive forces of Tanzania’s geographic, class and racial differences, Fatima is shielded from same because of her affiliation with the Indian community. Maria tells a very captivating story, one that holds Fatima spellbound, and also helps her to experience a rollercoaster of emotions and develop an awareness of the happenings outside her community.

T-Junction’s strength lies in a remarkable cast and excellent cinematography, but the film is peppered with unresolved storylines and underdeveloped characters: The cause of Maria’s injuries is as mysterious as the fates of the motley crew that makes her story so compelling. Who was the man who barged into Bhabi’s home and attempted to attack Maria, and why did Fatima resent Bhabi so much? Would Maria have had shared Fatima’s opinion about Bhabi if they had shared notes, considering that she was portrayed as a good mistress to Maria?

It’s possible that the filmmaker expects the audience to project their own thoughts onto the film and conclude the characters’ stories, but whatever his intentions, T-Junction is a relatable film whose message resonates beyond the span of a busy 3-way street.

Foyeke Ajao

---

When Ifeoma Chukwuogo's short film Bariga Sugar was screened last year at AFRIFF, one of the things that came to mind was that you can meet a friend in the weirdest places. In Bariga Sugar, it was a brothel located in Lagos. In T-Junction, it's a hospital in Tanzania that does the work of bringing Fatima and Maria together as friends. Like Ese and Jamil from Bariga Sugar, Fatima and Maria are from different worlds and have different realities, but there's a common ground that solidifies the friendship – the story of what happens at T-junction.

The 105 minutes movie tells the story of Fatima (Hawa Ally) who comes to the full realization of a lot of things after the death of her estranged father. Fatima is the daughter of Iqbal Hirji and has mixed parentage, as she is born to the Indian Iqbal and her Tanzanian mother (Mariam Rashid) who was Iqbal's domestic worker prior to their marriage. When she meets Maria (Magdalena Christopher) during a random visit to the hospital, she understands the contradictions of the society she lives in and this leaves her more conscious to happenings around her.

The film touches on a lot of things, most interestingly on racial discrimination in Tanzania. In the past, Tanzania has been pencilled as one of the countries hit with various racial discrimination scandals and this pretty much reflects in the movie. Fatima, who probably is within the same age bracket as Maria, is pretty oblivious to the society around her, because she’s privileged to be of mixed parentage. As all of this goes on, it answers to how years of economic divide between Fatima and Maria has set them both in different social classes.

Another interesting aspect to note about T-Junction is the harsh life meted out to the street merchants. These are people whose lives are dependent on street hawking, and yet the government is destroying their structures and killing them, all with little or nothing being done about it. In a way, the movie, too, throws jabs at the state of power and the hospital facility, to mention but a few. People who are born like Maria have come to get used to it and just rant about it. "We will always be under people's feet – whether dead or alive".

T-Junction is Amil Shivji’s directorial debut and has won him awards for the best feature film at the Zanzibar International Film Festival where it was screened as the opening film. It evinces the art of great storytelling from the start, taking you through the burial and mourning scenes of Iqbal, rituals which are attended by the Indian community. This already points towards the discrimination storyline the film gears for. The cinematography is great – especially the beach scenes where Maria is rested on the shoulders of Mussa first, and then Fatima eventually. The close-up shots of both Maria and Fatima are brilliant, as you're able to see their emotions and share what they are going through at the point. Not to forget the equally great dialogue, with one or two lines sneaked in for humor, even on a such a serious topic. Eventually, T-Junction ends decently but leaves you with a couple of unanswered questions.

Franklin Ugobude

---

Wrong Con (Charles Obi Omere, Nigeria, 2018)

The Accelerate Filmmakers Project sponsored by Access Bank PLC sprung up some top quality short films from the finalists of the project; one of those being Wrong Con, a story of two con men disguised as clergymen contracted to perform an exorcism on a young girl. The girl gets delivered of the evil spirit by some unresolved phenomenon. The evil spirit then taunts the con men, after they have been paid for their services. The filmmaker and one of the finalists in the contest, Charles Obi Emere, compactly combines spirituality and comedy, both strong reoccurring themes in Nigerian films.

The camera angles, choice of music, effects, acting and post production illuminate the story, lend it the right appeal and achieve the mandate of inducing laughter. The most engaging bit of the film is the dialogue between the con men in preparation for a pitch with their client (the father of the possessed girl). The end montage, a freeze animation-like effect also stands out as very innovative. It gives the needed comical effect to the film.

Although the filmmaker tries to offer a probable explanation for the scene of the exorcism and the rationale for the willing vacation of a body by the evil spirit, it didn’t really fit and felt like an imposition of clichéd beliefs from foreign witchcraft films. However, the run-in of the con men with the real con, the devil or demonic spirit who is known across all beliefs as a deceiver and who cannot be conned, gives the plot a deeper meaning even in the dominant comical theme. If the filmmaker had executed this sub-theme properly, he would have been able to give the short film more credence.

For a first attempt at a short film, Wrong Con has an interesting vibe and could be developed further into something bigger; a series maybe.

Olumuyiwa Akinkuolie

Kommentare zu „(Re)Views from Lagos – African International Film Festival 2018“

Es gibt bisher noch keine Kommentare.